“The public realm, as the common realm, gathers us together and yet prevents us from falling over each other, so to speak. What makes mass society so difficult to bear is not the number of people involved, or at least not primarily, but the fact that the world between them has lost its power to gather them together, to relate and to separate them.”

- Hannah Arendt from The Human Condition

Shifting circumstances and the introduction of digital technologies have outrun traditional typological definitions of urban public spaces such as plazas, squares, and parks. The digital age has elicited a new level of blindness and unconscious living within the city or, in Walter Benjamin’s words, “the space of distraction.” By neglecting the context of the built world around us including spatial relationships, environmental changes, and the passersby, we are diminishing our own authority and presence as humans and individuals within a collective society. This, by extension, results in a dismantling of the “space of appearance,” the space where we establish our existence within the public realm. Rafael Moneo explains that it is often these extreme changes in society that push a designer to develop a new typology to meet and respond to the shifting needs of society.

As designers, our agency lies in our ability to design and construct something “more permanent” than the fleeting activities that reside within them. The design must be stable and tangible but also sensitive and responsive to changing needs in order to consistently offer a “space of appearance” which ultimately grounds the public realm. This is a call for a new typology of the public realm. The typology must spatially intervene in our impersonal contemporary society to simultaneously relate and separate the individual and the collective in order to [re-]establish and facilitate a physical interpersonal interaction. The spatial construction will foster a productive tension between generic desires and specific materializations and simultaneously respond to and manipulate the fluctuating social and environmental conditions of the city.

We live in a society which is grossly-over connected through the digital realm. An increase in the sheer quantity and homogeneity of virtual connections has corresponded with a decrease in the quality and heterogeneity of physical connections thereby producing a problem of “simultaneous physical presence and situational absence” (Hampton 2010, 705). Superficial and impersonal networks have led to physical and psychological separation and consequentially, a decrease in the richness of interpersonal relations necessary to sustain society.

This change is most visible in the urban public realm where the exchange between individuals and the collective society is most palpable. Traditionally, “Participation in the public realm increases exposure to social diversity. This exposure may be manifest in the formation of larger, more diverse social networks” (Hampton 2010, 714-716). However, Hampton’s research on North American public spaces also reveals that the presence of Wi-Fi and mobile phone users significantly altered the dynamics and possibilities of interaction within the space. “The reduced attention to surroundings, in the form of people-watching, a focus on private, head-down activities, and limited response to stimuli from the environment suggest that wireless Internet users are exposed to significantly less social diversity in urban public spaces…” (Hampton 2010, 713). This increase in activity-oriented focus rather than environment or people-oriented focus has decreased the individuals’ level of consciousness creating a new type of blindness within the pre-established but now deepened “space of distraction” and de-valued “space of appearance.”

The promise of spontaneous “democratic engagement” traditionally offered by public spaces is threatened by technological users. Their virtual engagement reduces the number of people available for physical interaction. This “contextual effect” therefore discourages interpersonal interaction for all and “leads to the presence of silent spectators rather than potential participants” (Hampton 2010, 705-706). This thereby bestows technology with a powerful influence on interpersonal relationships within public spaces and ultimately results in fundamental changes in the character of urban public spaces for everyone.

For most people, the city becomes the backdrop or stage set for foregrounding our daily lives and is experienced in a “state of distraction” (Benjamin 1969, 239). Our first experience of a space and a city is unique and irreplaceable. It becomes distant and “incidental” with the absentmindedness of habitual use or activity. Anthony Vidler explains, “We seldom look at our surroundings. Streets and buildings, even those considered major monuments, are in everyday life little more than backgrounds for introverted thought, passages through which our bodies pass ‘on the way to work.’ In this sense cities are ‘invisible’ to use, felt rather than seen, moved through rather than visually taken in” (Vidler 2000, 81).

This new digital age has now deepened the pre-existing “state of distraction” and has rendered us blind to our surroundings, the spaces we pass through, and the people we pass by. Hidden behind technological screens, the city which was once in the foreground of our reality has shifted, seemingly permanently, to the background of our virtual existence.

Despite the ubiquity of technological distractedness, the design of physical space remains relevant and is a critical link to reversing the degradation of social relationships. As Nancy Baym states in her book Personal Connections in the Digital Age, it is not that technology is necessarily good or evil but it is changing social dynamics and it is surely not going away. So now, “From the social shaping perspective, we need to consider how societal circumstances give rise to technologies, what specific possibilities and constraints technologies offer, and actual practices of use as those possibilities and constraints are taken up, rejected, and reworked in everyday life” (Baym 45). By acknowledging the presence, evolution, and relationship of technology with society and the public realm we can design for it. Through design, we can establish a new way of seeing and a new level of consciousness which will allow us to navigate the city and interact with the population in a new and more meaningful way. Additionally, it will allow us to retrieve, in the words of Roland Barthes, a “third meaning” of the city which lies not in the concrete technologies, architecture or habits of our everyday lives but in the abstract power of individuals to appear explicitly and exist within the “space of appearance” in the public realm.The importance of the public realm lies in its role as the

However, within this deepened “state of distraction” and unconscious blindness, we have relinquished our power and our ability to appear explicitly. By giving up our vision and ability to “see” others within the public realm, we have given up our own ability to appear explicitly and therefore exist as humans, as individuals, as a part of a collective which once defined the “space of appearance.” Our abstract virtual lives have overridden our actual physical lives but our presence and power can be re-established through a tangible design and construction of the public realm.

Although experienced through infinite perspectives, design or spatial construction has the ability to ground our intangible lives and experiences in a physical reality. In the eyes of Hannah Arendt,

“The whole factual world of human affairs depends for its reality and its continued existence, first, upon the presence of others who have seen and heard and will remember, and, second, on the transformation of the intangible into the tangibility of things”

(Arendt 1958, 95).“The reality and reliability of the human world rest primarily on the fact that we are surrounded by things more permanent than the activity by which they were produced, and potentially even more permanent than the lives of their authors. Human life, in so far as it is world-building, is engaged in a constant process of reification, and the degree of worldliness of produced things, which all together form the human artifice, depends upon their greater or lesser permanence in the world itself”

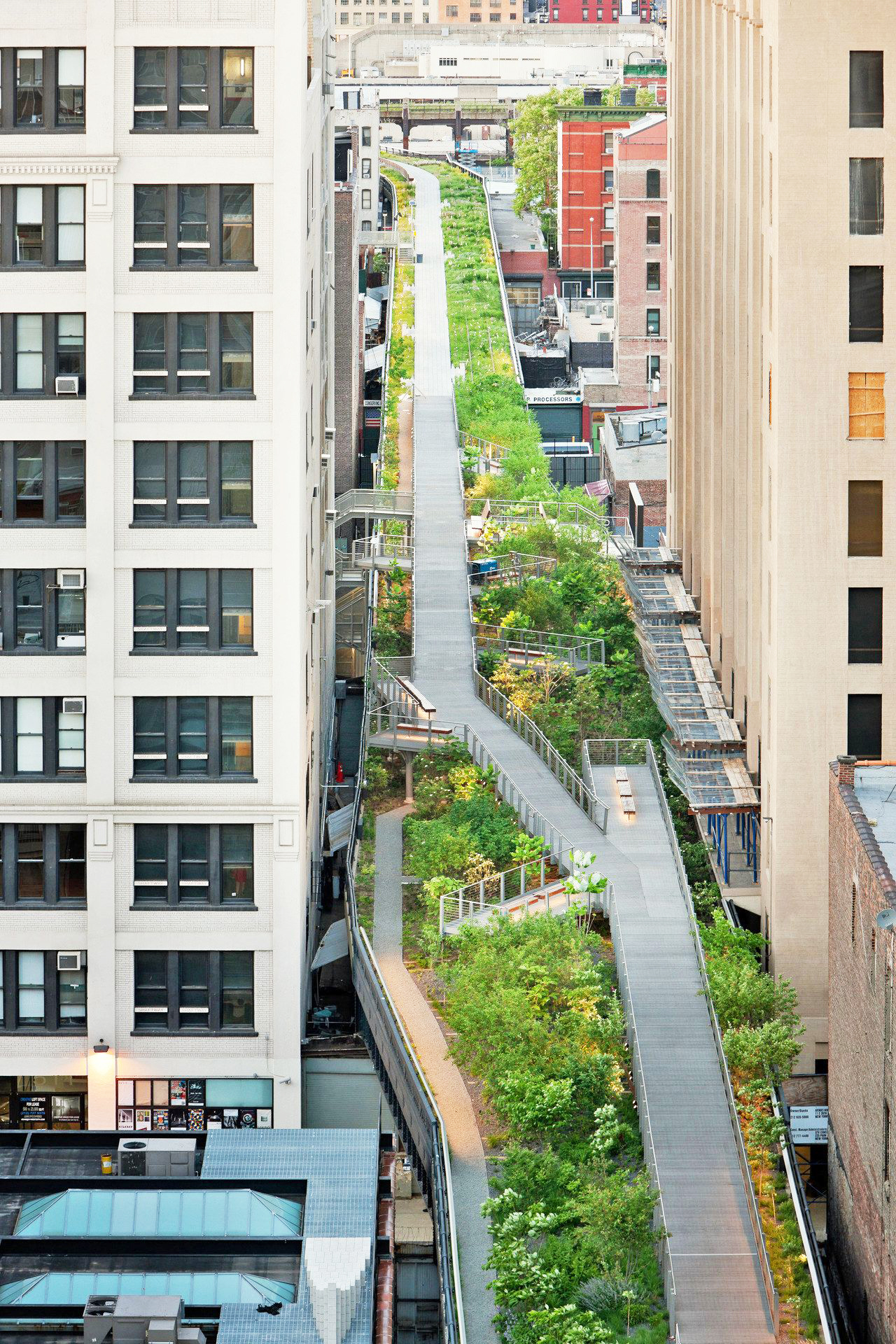

(Arendt 1958, 95-96).In recent years, we have seen the beginnings of an undeclared initiative to regain interpersonal exchange between the individual and collective. There has been a rise in unprogrammed, yet seemingly programmed, public projects such as the Highline in New York, Theatre Plaza in Antwerp and the Seattle Public Library’s “Living Room” in Washington. These projects often transform underutilized areas of the city to offer a particular condition: a place to gather, to relate, and to separate the individual and the collective. Through a conscious design of thresholds and sequence, the spatial design and organization establishes a legible and tangible place for the public realm to create a “space of appearance.” Flexibility and temporality enable interaction while maintaining the ability to respond to the ever-changing flow of people, technologies, environmental conditions, and spatial/programmatic needs. A multi-scalar, pluralistic approach to scale and proportions allows each of the projects to read as a cohesive whole (from the third person perspective) while still relating back down to the individual human perspective (first person perspective).

Given this new cultural moment, interest, and active search for new interpersonal spaces in combination with the shifting technological and social circumstances, we can identify a need for simultaneous urban, architectural and political intervention. Once again, this is a call for a new typology of the public realm – one which spatially intervenes in our impersonal contemporary society to [re-]establish and spatially facilitate a physical interpersonal interaction [relation and separation] between the individual and the collective. The multi-scalar design will foster a productive tension between generic desires and specific materializations and simultaneously respond to and manipulate the fluctuating social and environmental conditions of the city.

In the past, public space typologies have indicated specific formal or structural attributes along with public ownership and happenstance program. Traditional public space typologies might include plazas, parks, markets, arcades, train stations, public libraries, and more. For example, European plazas like the Plaza Mayor in Madrid, Spain, were typologically defined as the resultant space created by the boundaries of surrounding building facades. Their role as a place of public exchange evolved over time and was a result of its public ownership and its status as an interstitial space with a lack of specific use. The public began to define its role and therefore influence its architectural features. The typology began as an unintentional left-over space but eventually evolved to be a designed void space for the public realm. Attached to these unstable historical ties, plazas became their own self-referential typology of the public realm with specific formal attributes and aesthetics. However, the new typology of the public realm is much more intentional and far-reaching because it is grounded in the architectural agency to both influence and respond to social activity rather than one or the other.

In contrast to the rigidly defined traditional public typologies of the past, this new typology does not indicate form, program or ownership. We can learn and borrow from these traditional typologies but we must respond to the shifting circumstances of digital distractions and impersonal relations to create a new, better informed typology of the public realm. As Moneo states, “…the very concept of type…implies the idea of change, or of transformation” (Moneo 1978, 24). Type implies change and is often a reflection of the stability or instability of society. It will be designed for and derived from both the individual and the collective.

Consequently, it is not necessarily a park, a plaza or a public library. Nor is it necessarily a publicly or privately owned property. The spatially and intentionally framed condition of exchange between the individual and the collective and the fluctuating social and environmental context is what makes it typological. The defining attributes of this typology are established through a new sensibility and spatial approach to:

01_threshold + sequence or a way of making space legible and accessible within the larger urban context,

02_flexibility + temporality in relation to the constantly changing social and environmental circumstances,

03_scale + proportions in direct relation to the pluralistic collective and each individual.

“To be revolutionary for the architect should mean something more than promoting a perversion of taste. It should involve a revolution in the way people live; it means using architecture as a way of breaking down the established social order” (Goodman 1971, 130). This proposal is not a nostalgic pursuit to restore the public realm and Parisian arcades of the past, a selfish aesthetic endeavor, or devious ploy to expel all technology from public spaces but, instead, is a new take on new circumstances – framing a new typology and the role of design in enabling a new vision for the “space of appearance” within the public realm. It utilizes typology as “the framework, the context within which we operate” (Colquhoun 1969, 74). It acknowledges the fluctuating state of the digital age and its resultant blindness and decreased physical interaction within the deepened “space of distraction.” By creating an urban design and architecture which is simultaneously responding to and shaping behavior in the public realm, it can begin to reconstruct a new, more relevant “space of appearance” necessary to the continued existence of society. Design has the agency to enable a new vision for occupation and use of public spaces, fostering interaction, relation and separation between the individual and the collective, thereby grounding the fleeting public realm within a “more permanent” identifiable place.

Arendt, Hannah. The Human Condition. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1958.

Baird, George. The Space of Appearance. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1995.

Barthes, Roland. “The Third Meaning: Research Notes on Several Eisenstein Stills.” Image, Music, Text. New York: Hill and Wang, 1977. 44-68.

Baym, Nancy K. Personal Connections in the Digital Age: Digital Media and Society Series. Cambridge: Polity Press, 2010.

Benjamin, Walter. “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” Illuminations.

Ed. Hannah Arendt. Trans. Harry Zohn. New York: Schocken Books, 1969.

Colquhoun, Alan. “Typology and Design Method.” Perspecta 12 (1969): 71-74.

Goodman, Robert. After the Planners. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1971.

Hampton, Keith N., Oren Livio, & Lauren Sessions Goulet. “The Social Life of Wireless Urban Spaces: Internet Use, Social Networks, and the Public Realm.” Journal of Communication 60 [2010]: 701-722.

Madanipour, Ali. Public and Private Spaces of the City. New York: Routledge, 2003.

Moneo, Rafael. “On Typology.” Oppositions 13 (1978): 23-45.

Vidler, Anthony. Warped Space: Art, Architecture, and Anxiety in Modern Culture. Boston: The MIT Press, 2000.